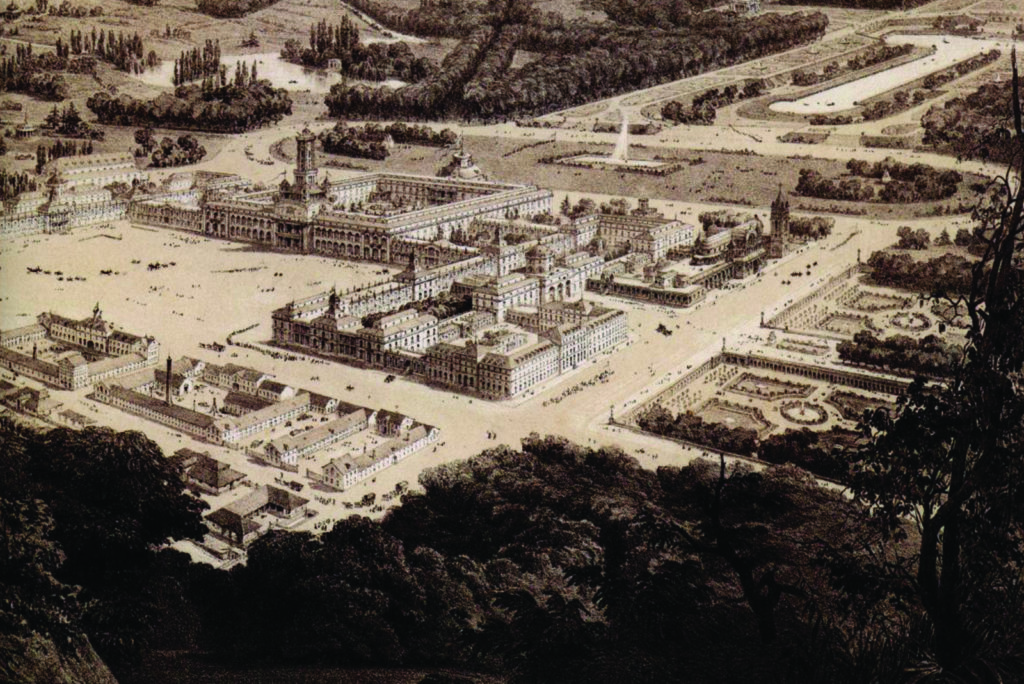

Considerant, Fourier’s most ardent and astute student, had tried to build a socialist and community colony (named a phalanx by Fourier) outside of Paris in 1852. Still, all such endeavors were forbidden by Napoleon III, the last emperor of France (1852-1870). The radical leader was exiled to Belgium for harsh criticism of the new leadership, but he eventually settled in the United States to pursue his professional and personal goals. After traveling from New York through numerous western states to north Texas for six months, he decided to build his new phalanx on the limestone cliffs across the Trinity from Dallas. On his return to Europe, Considerant established the European and American Colonization Society of Texas to generate money for the colony and allocate the funds they received with the release of the book “In Texas” Au Texas,

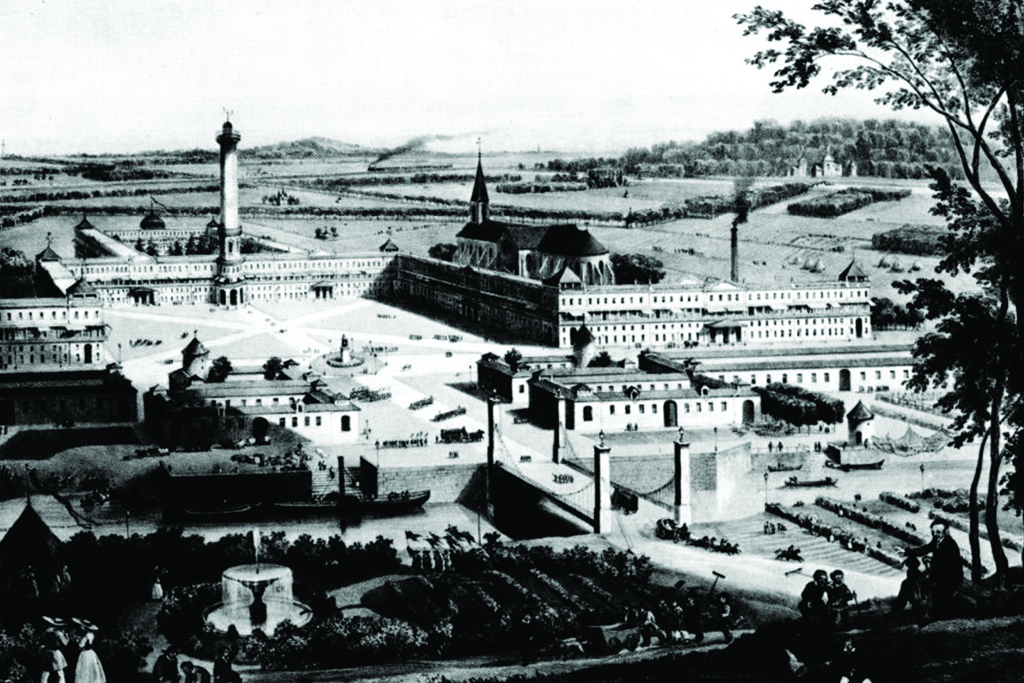

A large number of northern Europeans joined Considerant’s endeavor after hearing about the success of Au Texas. The vast contrasts among the group’s individuals served as a defining feature. Some of them were “bored to death” and wanted to be revitalized by “the renewing energy of nature.” Others were “genuine believers” in socialism, while others were “weary of turmoil and recession back home.” They were educated in subjects as broad as business and geology, but few had rural agricultural experience. Despite the difficulties and setbacks faced on their journey to the socialist paradise of Texas, the settlers, who numbered around 400 by the end of 1856, set to work with determination to construct a two-story central structure, a commissary, and a kitchen. Behind this outward show of socialist unity, La Réunion was doomed to the same fate as the rest of the American phalanxes due to class conflict and economic crisis.

Colonists placed the responsibility for La Réunion’s quick decline in 1856-1857 squarely on Considerant’s personality and management, but the failure was also rooted in the inherently unstable foundations of Fourier’s ideals. The phalanx’s foundation may have been the “law of love,” but it was anything from democratic, instead being led by the president and the directors with an iron fist. After losing the support of the colonists, President Considerant grew more authoritarian. He became “a morose man, unable to speak and grew terribly despondent” after suffering a loss of power that was entirely his own fault. Alcohol and morphine helped Considerant get through his severe periods of depression and self-doubt. As Considerant began to loosen his grip on the colony and spend longer and longer amounts of time abroad, tensions rose among the colony’s craftsmen and professional men about who should be in charge of La Réunion. The colony’s poverty and financial reliance on the Dallas community cast a growing veil of misery over La Réunion and paved the way for the person who would dominate the island’s last days. Upon arriving at La Réunion in 1855, the obstinate French army doctor Augustin Savardan started to challenge the authority of the island’s governor, Considerant, who saw Savardan as “conceited, touchy and of narrow spirit.” The doctor said that the president was “eating up the resources or exploiting the laborers,” and he accused Considerant and his allies of corruption, mismanagement, and favoritism. Saying that “each one must become his own justice,” Savardan immediately became the face of the traitorous resistance. Both sides “became more resentful and blamed one another for all the awful things they had endured,” resulting in a schism in the colony. As a consequence of this uprising against the colony president, there is now a tense stalemate rather than a victorious party. Without the “immunity of collectivism” to survive “the drive of individuality,” La Réunion withered and died, and its people dispersed to other parts of Europe or the expanding Dallas metropolitan area

Although La Réunion did not remain in Texas for very long, it had a lasting impression on the state and, in particular, the Dallas area. Considerant’s outstanding personality elicited immediate reactions, both favorable and negative, from his adoptive motherland. As a result of Horace Greeley, the left-leaning owner and editor of the New York Tribune, broadly positive stories of the Fourerist initiative were published there. The first efforts of Considerant were lauded in the Dallas and Galveston newspapers in the belief that the socialist colony may introduce a “higher level of civilization” to rural America.[2] As a consequence of Considerant’s constant promotion of a positive image of his colony, the Texas Know-Nothing Party and its main newspaper, the Texas State Gazette, became informed of La Réunion and replied by printing several negative articles about the French socialists. The furious editor of the Austin newspaper depicted the colony as a threat to Texas’s democratic democracy by portraying them as revolutionaries, political quacks, abolitionists, and, worst of all, Catholics.[3] As early as February 1855, this Know-Nothing group labeled both Considerant and those planning to move to his colony as “a violent band of treasonous, lawless, foreign abolitionists who were attempting to undermine the foundations of society” whose plans could not be put in place “without producing bitter and unyielding prejudices and animosities among our indigenous citizens.”The same newspaper labeled Considerant’s supporters as “a mischievous portion of the community” on June 2, 1855, saying that their “wild beliefs would not long survive the test of experience.

It was clear that the public’s opinion of Considerant’s political actions had shifted dramatically during 1855, so when he returned to Dallas from a trip to Europe, he went on the propaganda attack. After writing a pamphlet called European Colonization in Texas, in which he rebutted the Know-Nothings’ claims point by point, he tried to put his business on the solid financial and political ground by asking the Texas legislature for a land grant in exchange for the money his group had spent relocating so many colonists to the Dallas site. In an effort to salvage something from his journey into the nascent Texas political arena, Considerant had the European-American Colonization Society established in its new home state after the Democratic majority in the state legislature and the governor’s office rejected his request

The assaults against the Dallas socialists by Texas newspapers reached a peak in 1857. However, by this time, Considerant had lost the desire to resist them, and so he was compelled to confess that his efforts had been futile. Accepting responsibility for the failure at La Réunion was not in his nature. Instead, he rehashed previous events in a booklet titled Du Texas, “From Texas,” where he placed the blame for the Dallas fiasco on xenophobic Texans and self-centered colonists while avoiding responsibility for his own dictatorial and indecisive style of leadership. However, the old campaigner was not deterred, and he tried again, this time in Uvalde, West Texas, before returning to France, where he was revered as a socialist legend until his death at the dawn of the twentieth century.

La Réunion was therefore never really solvent, and its trading deficit with Trinity merchants caused it to quickly rack up a massive deficit. Within a few months of their entrance, the “workers of the future” (des ouviers de l’aviner), as they referred to themselves in their song “The Immigrants” (Les Emigrants), had created a butcher shop, sawmill, and community store, all of which were dependent on American capitalism. Wild muscadine grapes thrived on the limestone uplands where the colony was established, and some of the settlers even tried their hand at winemaking with them.

Although Dallas came to value the unique talents that immigrants from other countries contributed to the area, the corporate structure of La Réunion caused legal problems for the colony that persisted for almost a decade after it was dissolved in 1858. The European and American Society for Colonization was structured as a business with Considerant at the helm of the board of directors to oversee the use of capital raised through stock sales. As expected, the colony quickly burned up the first year’s budget despite the fact that the board was stationed across an ocean from the colony’s executive director. Droughts, unusual cold periods, and catastrophic crop failures meant that Le Réunion had no way to repay its obligations, much alone the interest accrued on those payments. During the second half of 1855, contractors and carters who had sold the colony items or carried its members and their possessions from Houston to Dallas filed lawsuits against Considerant and Cantagrel for unpaid services. Surprisingly, some of the people involved in these lawsuits were indeed colonists. Each lawsuit had detailed invoices totaling over $1400 provided by the plaintiffs. The colonial delegates’ reaction to these demands was that the society’s Belgian board of directors needed to review these kinds of measures. When the defendants refused to pay up immediately, the plaintiffs reacted aggressively and correctly by pointing out that no such organization existed at the time under Texas law and so they demanded immediate payment in cash. The plaintiffs were dissatisfied with the outcome of their day in court despite “expenses expended in traveling, illness, and sacrifices of property and time,” and finally accepted the colony’s pledge to clear its obligations on the installment plan. However, it is extremely improbable that this legally binding contract was adhered to after the colony site was sold during the final years of the American Civil War, as shareholders in the venture were never properly compensated for their losses and a number of the colonists were involved in civil lawsuits until 1890 over the division of La Réunion’s lands.

Even though La Réunion was in ruin and completely abandoned in 1858, the territory “had been a benefit to the country, supplying outstanding employees in valuable employments,” After the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865, the town of La Rèunion became a beloved and often-remembered vestige of Dallas’s history, although consisting mostly of a ghost town save for a few isolated farms. The stone archway, director’s house, and community shop built so quickly in 1855 under the direction of J.F. Barbier and Ferdinand Michel were still standing, and they would remain so for over a century until they were destroyed by the nearby Lone Star Cement Company.

References:

Victor Considerant. Au Texas. 245-250.

Jonathan Beecher, Victor Considerant and the Rise and Fall of French Romantic Socialism.

Kagay, Donald J. “The Utopian colony of La Reunion as a social mirror of frontier Texas and icon of modern Dallas.”

Ann Irene Sandbo, “Beginnings of the Secession Movement in Texas,” SHQ Vol. 18, no. 1 Jul. 1914

Darrell W. Overdike, The Know-Nothing Party in the South. Louisiana State University Press. 1950

Victor Considerant, European Colonization in Texas: An Address to the American People (New York: Baker, Godwin, 1855)

Hammond, W. Jackson, and Margaret F. Hammond. La Réunion: A French Settlement in Texas. Royal Publishing Company, 1958

Rondel V. Davidson, “Victor Considerant and the Failure of La Réunion