The influences of Joseph Proudhon

“I am an anarchist” and “Property is theft!”

Woodcock George. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon; A Biography.

According to Jonathan Beecher, Proudhon placed great significance on the events of the 1848 revolution. To paraphrase, it sucked him into a whole other existence. Because of this, he gained not only journalistic clout but also the status of people’s spokesperson. That made him an easy target but also exposed him to a far larger audience than before. He was made fun of by Thiers and political cartoonists of all stripes, becoming the scapegoat of the Right. Nonetheless, during 1848, and particularly after the June Days, he became the voice of “the people” who felt deceived by the revolution.

Proudhon was a vocal, though not always consistent, opponent of President Louis-Napoleon following his election. He was finally convicted of crimes against the government. So he went to Belgium, but then he came back to Paris and was caught on June 5th, 1849. Three years passed while he was locked up for the greater part of that time. He could keep himself occupied while incarcerated by editing two newspapers, penning his “confessions,” and two other significant works, all owing to prison reforms ironically instituted by Adolphe Thiers. Proudhon’s publications helped him begin to locate himself in relation to the revolutionary heritage while also developing a sharp criticism of the revolutionary government and the extreme “Jacobin” Left.

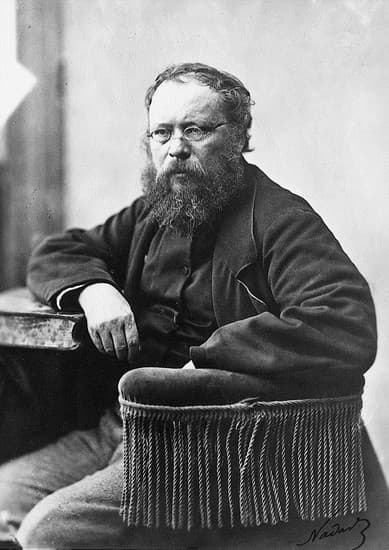

While most prominent French radicals of the 1830s and 1840s had urban backgrounds, Proudhon’s family still lived in the countryside. Coopers in Franche-Comté build wine and beer barrels; his father became a brewer and innkeeper. Proudhon worked as a cow herd and a cellar boy in his father’s bar before becoming an apprentice to a printer in Besançon at the age of eighteen. Though Proudhon started his secondary education at the Collège de Besançon, a top-notch institution even by today’s standards, he did not finish there and relied to some extent on his own scholastic initiative. His employment as a proofreader of religious texts seems to have been the primary source of his understanding of theology, as well as the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew that he learned in the process. At age 29, he received the Pension Suard, a three-year fellowship from the Académie de Besançon given to talented young men from humble circumstances, and so began his successful career as a provincial intellectual. Proudhon’s self-description in his pension application reflects the importance he placed on his heritage. Beecher claims that Proudhon was influenced by his working-class upbringing and the idyllic vision of country life he had experienced as a youngster.

His more developed ideas seem to represent an ongoing quest to reclaim that ideal. Although Proudhon was the first French intellectual to use the term “anarchist,” he preferred to discuss his “socialist” beliefs, taking pride in the fact that they had “got the baptism” from a traditionally educated society. When he was in the Collège de Besançon, he shared a dorm with Fourierist Victor Considerant. Still, he never felt a connection to Considerant or any of the other romantic socialists of his day. In 1849, he boldly declared that he had “never sought illumination from the socialist écoles” in his early endeavors to learn more about political economics and the issue of poverty. 2 Therefore, he rejected both the state socialism of Louis Blanc and the communitarian socialism of the Fourierists when formulating his own theories. Any effort to bring about social change from on high, in his opinion, was certain to fail. He insisted on the need to give employees a say in the production process and foster an environment where people might take the initiative to build their own community.

In 1840, Proudhon issued a scathing critique of society as a whole. He saw a new “mercantile and landed aristocracy, thousand times more rapacious than the old aristocracy of the nobility” ruling and exploiting the order. Proudhon was a partner in a modest Besançon printing firm at this period. Because of the company’s lack of success, he sold it in 1843 and relocated to Lyon, where he became an agent for a shipping company. The silk weavers, or canuts, who had been at the forefront of the French workers’ movement since the 1830s, were his allies in Lyon. In the middle of the 1840s, Proudhon was working in Paris when he met a group of exiles from other countries. Among them were a few young German Left-Hegelians and “four or five Russian boyars.” Among the Russians was the radical thinker Mikhail Bakunin; among the Germans was the young radical named Karl Marx at the age of 26.

.

Other Proudhon’s collected works

References:

Woodcock George. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon; A Biography

Woodcock, George. “Anarchism.” In The Invisible Hand, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1989

Beecher, Jonathan. Victor Considerant and the rise and fall of French Romantic socialism